Among the very few items

I have from the archives of my grandparents’ life is a letter that personalizes this 1918 notice that appeared in the Journal of American Medical Association:

“The 1918 has gone: a year momentous as the termination of the most cruel war in the annals of the human race; a year which marked, the end at least for a time, of man’s destruction of man; unfortunately a year in which developed a most fatal infectious disease causing the death of hundreds of thousands of human beings. Medical science for four and one-half years devoted itself to putting men on the firing line and keeping them there. Now it must turn with its whole might to combating the greatest enemy of all – infectious disease,” (12/28/1918).

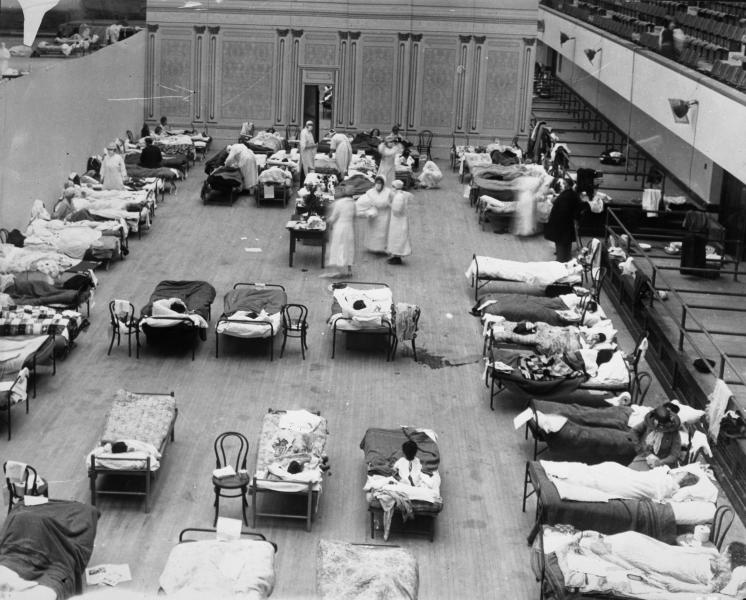

An estimated 675,000 Americans died from the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 – 10 times as many as would lose their lives in World War I that ended that same year.

My grandmother, the oldest among her siblings, gave birth to my father that year – the sixth of her seven children.

Two of her sisters were in school in a small Southern Alabama town about 35 miles from where she, my great-grandmother and the rest of the family lived pursuing the lives of cotton farmers.

It was from there that the urgent letter of Dec. 6 was dispatched via “Special Delivery,” which added 10 cents to the usual cost of postage that year. Even then it took five days for the correspondence to make the 35-mile trip.

The one-page letter to my grandmother from her sisters revealed the urgency for the help they needed that grew from the fear of becoming infected with the flu that had sickened others in their school.

They pleaded for their sister to intervene with their mother to “send a car” to pick them up and bring them home.

The letter explained that the headmaster of the school “… will not let us go on the train” [no one could ride a train anywhere without a doctor’s certification that they were not sick]. “We could stay here but it would cost 70 cents plus medicine if we were to get the flu, so you can see why it would be wise for us to go.

A post script was added on the back:

“She had better write a note and send by whoever comes for us … we want to come home. We have just heard we would have to pay a nurse $35.00 per week if we get sick so please send for us.”

While I don’t know why the two girls asked their sister to intervene for them with their mother instead of addressing the letter directly to her (maybe she couldn’t read), but the historic world-wide pandemic now seems personal to me.

I also don’t know whether they made it home or if any of them became infected with the deadly flu. But the “what ifs” make for interesting speculation

The particular strain of the disease

was devastating for 15- to 35-year-olds, resulting in a death rate 20 times higher in 1918 than in previous years. Physicians of the time were helpless against the powerful agent that led to some dying within hours of developing the flu.

Had my infant father been lost, nothing or no one that his life was responsible for developing would have ever occurred.

As profound as that seems to me personally for something that might have happened almost 100 years ago, the reality is that all of history was altered by what remains the most devastating epidemic in the annals of medicine.

Estimates are that somewhere between 20 and 40 million people worldwide died of influenza in a single year. That’s more than in four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351.

It was a global disaster. No wonder my great-aunts, teenagers at the time, wanted to come home. Where they felt they would be safe in frightening times.