Members of the U.S. Army Special Forces have long served our nation, often in combat under extreme adversity. Dozens have received the Medal of Honor for service above and beyond the call of duty.

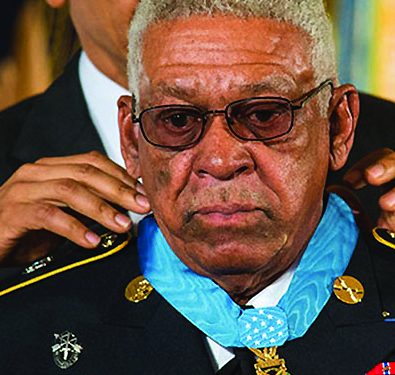

One outstanding Special Forces Medal of Honor recipient, Melvin Morris, was also a pioneer, becoming one of the first Green Berets in 1961. His courageous action in Vietnam in 1969 earned him a Medal of Honor that he would not receive until 2014.

Born on January 7, 1942, in the rural town of Okmulgee, Oklahoma, Morris was one of eight children. As a young man he enjoyed sports and outdoor activities such as hunting and fishing. Having trouble finding a job after he graduated from high school, Morris joined the Oklahoma National Guard and then transferred to the U.S. Army.

“Being in the military,” he later remembered, “was better than being in trouble.” After finishing boot camp and Airborne training, Morris learned about the formation of the “Green Beret” Special Forces Group and was fascinated by the challenges that it offered.

Though small in stature and weighing under 120 pounds, Morris excelled in training, and became one of the first Green Berets in 1961.

Rising to the rank of staff sergeant, Morris entered his first tour of duty in Vietnam in 1969. There he served with the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne). On September 17, he was placed in charge of the Third Company, Third Battalion of the IV Mobile Strike Force entering action near Chi Lang in the Republic of Vietnam.

During the engagement, Morris learned that one of his fellow team leaders had been killed in action near an enemy bunker. He advanced with two other men to retrieve the body and a top-secret map that they could not permit the enemy to recover.

As the three Americans approached, however, an enemy machine gun opened fire, wounding both of Morris’s men. He helped them to safety, and told them to deliver suppressing fire while he went to retrieve the body on his own.

As Morris approached the body, he was once again taken under fire by the enemy. Realizing that he would have to neutralize the enemy positions, Morris single-handedly destroyed four bunkers with hand grenades. He then reached the body and, driving back attacking enemy soldiers, attempted to return with it to his lines.

In the process, Morris was seriously wounded three times. He nevertheless succeeded in bringing the body — and the map — to safety before he was medically evacuated.

Morris returned to Vietnam for a second tour of duty not long after this action, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross in 1970. Two years later, he retired from military service and focused on raising his three children.

After three years of civilian life, however, Morris opted to return to military service, eventually rising to the rank of sergeant first class. He finally retired from military service in 1985, although symptoms of post-traumatic stress made his return to civilian life difficult.

Almost 30 years later, Melvin Morris received a surprise phone call from a representative of the U.S. Army, who told him to expect another phone call from somebody holding a high position in the government. When the phone call came, the man on the other end of the line was none other than the President of the United States, Barack Obama. Morris fell to his knees when he learned from the president that he would be receiving the Medal of Honor. “The government said it was because of racial discrimination that I didn’t receive the Medal of Honor earlier,” Morris recalled, “but I didn’t ever question it; I was just satisfied with what I had.”

Morris received the Medal of Honor at the White House on March 18, 2014. “It was an exhilarating feeling, I just can’t describe,” he said. “But I told myself that now, I’ve got a lot of work ahead of me because I have a message to share. Young children need to know that people are out there putting their lives on the line for them every day.”

Edward G. Lengel, Ph.D., is the Chief Historian of the National Medal of Honor Museum.