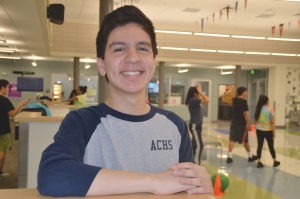

As scores of exuberant students glide across stages this month and next to obtain either high school diplomas or college degrees, signifying years of academic due diligence, Esteban Hurtado will be one of the more notable ones. He’s actually earning one of each.

The high school diploma is from Arlington Collegiate High School, the early college specialty institution sitting just east of Tarrant County Community College Southeast that was featured last month in this magazine – and that is graduating its first class.

The degree, an associate’s, is courtesy of TCC. While the 17-year-old mulls over where he’ll go in the fall – maybe Texas Christian University, maybe not – what’s certain is that he’ll step foot on somebody’s campus as a junior.

With college costs so high they could bankroll a small country, putting oneself in this sort of economically pleasing position has made Esteban a hero in his Arlington home of seven brothers and sisters.

At TCU, Esteban received the prestigious Chancellor’s Scholarship, which pays tuition and fees that, for any of us mere mortals, would represent a $287,000 hit.

What Esteban has achieved – jumping ahead two years, technically – is becoming more common, partly because a number of cities are establishing these schools where within a couple years students can blow through a four-year high school curriculum, freeing them up for college coursework.

Esteban took classes at TCC during his junior year. The following year he was taking Abnormal Psychology and a Speech course for Engineering majors at the University of Texas at Arlington, blending in like a regular collegian.

He is a smart kid who ACHS teachers and Principal Ben Bholan describe as “laser focused,” yet he’s still only 17. Most teens I know are just now trying to figure out the college thing; for Esteban, he was doing this back as an eighth grader at Christine Barnett Junior High School.

Which brings me to this: there’s an elephant-in-the-room sociological question to be asked here, and that involves the fast tracking of education. Money is certainly a reason to do it; shaving off two years of college is monetarily enticing.

Yet even Arlington ISD Superintendent Dr. Marcelo Cavazos says that the early college route “is not for everybody,” and he was talking about students who want the traditional high school experience of sports and bands and homecoming dances and proms.

Esteban got some of that at James Bowie High School, his neighborhood school, and says he never felt socially deprived. He’s even playing the cello again.

Early college students also get a jump on adult-like responsibilities. College forces you to take full ownership of your time since it is no longer dictated by others; college professors don’t track you down for late assignments. They simply slap you with a zero. You’re told in high school what’s expected. In college, it’s just expected.

Bholan says inching into college life at TCC helps the transition, and Esteban agrees, saying at UTA, “I felt pretty comfortable. No one knew I was technically a high school student, and I never felt overwhelmed or out of place.”

So Esteban has an associate’s at 17, the possibility of a bachelor’s degree at 19, medical training that will have him working as a full-fledged physician’s assistant, his career choice, by the age of 22 or 23.

Last month while visiting with second graders at Sam and Barbara West Elementary, Grand Prairie Mayor Ron Jensen emphasized the importance of a low-key, enjoyable experience. “Listen to your teachers, but have fun,” he told them. “You’ll be working hard soon enough.”

Some will be targeted and placed in “gifted” classes and later put on the academic fast track.

Remember: Dr. Cavazos is right. It’s not for everybody.

For Esteban, though, it is clearly the right fit.

Columnist Kenneth Perkins has been a contributing writer for Arlington Today since it debuted. He is a freelance writer, editor and photographer.