It has been a long journey to restoration, but retired Arlington arborist Sandy Rose has almost reached the finish line with his 1914 Buick B-24 Roadster.

Trying to put a rare 104-year-old Brass Era car back together proved to be a project that has spanned three generations and included a search for parts and information that has crisscrossed the country and reached all the way to Australia.

Sandy’s first memory of seeing the car was when he was only eight years old in his grandfather’s garage in Gowanda, N.Y., sitting next to his 1909 Sears Motor Buggy that we featured here four years ago.

His father had bought the car for $350 in 1951 and had begun its transformation back to original specifications from when it had been used as a delivery vehicle for a liquor store in Buffalo, N.Y.

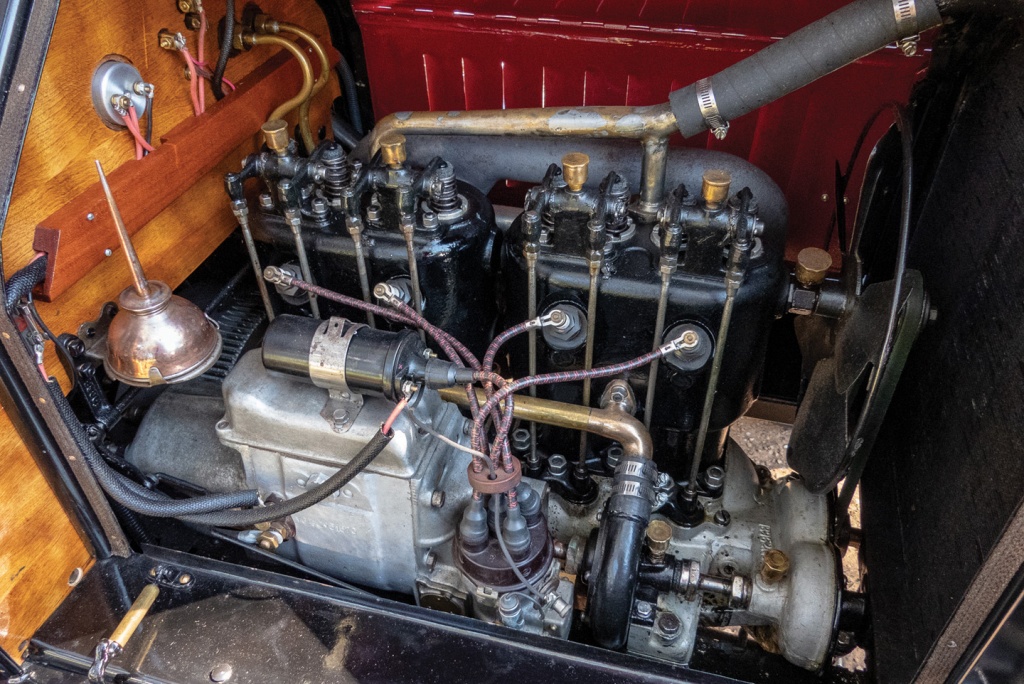

Work had included replacing the interior woodwork, cleaning up the frame, doing some body and fender work, then rebuilding the 4-cycle engine that delivered 22.5 horsepower – a feat that confirmed some quite remarkable engineering dating back to the development of the horseless carriage.

By the mid-1970s the car had been transferred to Sandy’s brother, Wayne, in Eden, N.Y. Wayne worked on it in his limited spare time and the automobile remained in his possession for the next 34 years.

Then came the time in 2010, Sandy describes, “Still the ‘new guy’ in the North Texas Regional Horseless Carriage Club of America, I had theprivilege of my first tour, and I savored the open-air driving, the sounds oftappets, smells of smoke, oil and gasoline.

“I emailed some photos of the tour to Wayne and said, ‘I am hooked on this hobby.’”

Soon his brother made him a deal he could not refuse, and Sandy informed his wife, “We have a new car!”

“I started the slow process of research about B-24 Roadsters, lurking in the Brass Buicks site, and joining the Buick Club of America. New tires were acquired and the radiator re-cored. The Marvel carburetor was rebuilt, resulting in a beautiful combination of a nickel and brass piece of art.”

Sandy located a restored B-24 in Dallas and, getting to know its owner, he used his example to slowly determine missing parts and identify where various loose parts he had were supposed to go.

Then three years ago, he found another in Newberry, Calif., and began to share photos and data with its owner, who was also nearing completion of his own restoration.

Recently Sandy has been exchanging information with a fellow owner in Australia who has less to work with than he does. “We keep learning the differences between the U.S.A. and export Buicks of the era.”

The scarcity of the models can be explained by the processes of rust, wood rot and scrap drives in WWI and WWII having reduced the B-24 survivors to a rare status.

“Out of the 3,126 plus 239 exports that were produced by Buick, I can only find about eight listed in club directors or in museums,” he concludes.

His latest finds in working to complete the long-term project include side and tail lamps, throttle and spark controls, hickory wood wheels and more.

So, the result we see now is pure joy shared with car lovers and enthusiasts wherever and whenever they get to see this two-seater marvel of early means of transportation that transformed the country’s principal way of getting around.

While today’s technology includes features and performance characteristics unimaginable to early car makers, it’s just plain fun to take a ride in one of the cars where it all began.

Driverless cars may be the wave of the future, but looking back a hundred years is pretty cool, too.