In May 1945, the 11th Armored Division of the US Army liberated Mauthausen Camp, one of more than 44,000 camps and other incarceration sites created under the Nazi regime in Europe. Of the thousands of Jews and political prisoners was a young Hungarian Jew named Tibor Rubin. The fifteen-year-old survivor made a promise to himself that he would emigrate to the United States and become a “G.I. Joe.”

Born in Pásztó, Hungary in 1929, Rubin was one of six children. By 1944, Rubin’s oldest brother had been conscripted into forced labor while his brother Emery attempted to flee but was captured and sent to the Mauthausen camp. Rubin’s father wanted him to avoid a similar fate, so Rubin left home at fourteen for Switzerland. Captured near the borders of Italy and Switzerland, Rubin was sent to Mauthausen where he was reunited with his brother Emery in the winter of 1944.

After their liberation in May 1945, Rubin and Emery returned home to Pásztó, where their sister Irene was waiting for them. Of their immediate and extended family, only Tibor and four of his siblings survived. After several years in a displaced persons camp, Rubin emigrated to the United States in 1948, followed by Emery and their sister Irene.

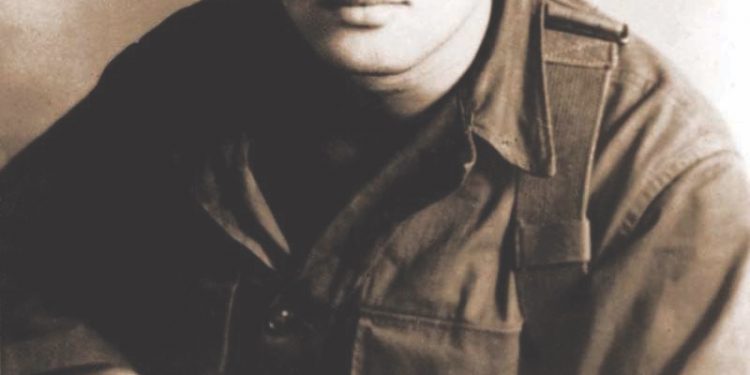

In 1948, Rubin began his attempts to join the US Army. With little knowledge of English, Rubin failed the language exam on his first try. He tried again the next year, and with some “help” from his fellow test takers, passed and was able to enlist in the US Army. He was finally a GI Joe. Unfortunately for Rubin, postwar peace was not to last long.

In June 1950, war broke out in a divided Korea, and the United States, as part of the United Nations, committed its military to pushing North Korean forces out of the southern half of the country. Part of the 8th Cavalry Regiment, First Cavalry Division, Rubin was part of the US forces committed to the growing war in Korea.

Rubin served under a sergeant who regularly gave him incredibly dangerous assignments. One of these left Rubin to defend a hill alone fending off a steady flow of North Korean forces for 24 hours. By the fall of 1950, most of Rubin’s unit had been captured or killed. Rubin, wounded numerous times, became a prisoner of war in November.

Where many of the young prisoners found it difficult to adjust to prison life, for Rubin, the mistreatment and deprivation was nothing new. He had been liberated in 1945 barely conscious, and terribly ill with dysentery. Rubin’s experiences in Mauthausen equipped him with the skills to survive imprisonment once again, and this time, to help those around him.

Fellow prisoners reported that Rubin would sneak out at night, risking his life by leaving the camp to scrounge for food from enemy supply depots. Rubin was always looking for opportunities to do good deeds for his fellow prisoners and encouraging them that survival was “mind over matter” through days and weeks of starvation. At one point, the communist forces holding Rubin captive learned he was Hungarian. They offered to send him back to his “People’s Republic,” as Hungary was then communist. Rubin refused—his desire was to be freed and return to the United States.

After two and a half years in a prisoner of war camp, Rubin was returned to US custody in a prisoner of war swap April 21, 1953. Suffering from a severe leg wound, he was carried on a stretcher and flown to South Korea. Upon his arrival, his story began to gather momentum. Rubin, a twenty-three-year-old immigrant who had volunteered to join the US Army, had been a prisoner in two wars. The story made newspapers across the United States, with Rubin’s face splashed across newsprint from coast to coast.

On November 27, 1953, Tibor Rubin’s dream came true — he became a citizen of the United States. Rubin had only been back in the United States for about six months, and his newly gained citizenship made newspaper headlines. But after the joy of citizenship, Rubin settled down into life, rarely speaking about his experiences in either war.

In the 1980s, men Rubin had served with began to protest that he had not received the Medal of Honor. There were rumors he had been recommended, but the recommendation had been rejected by his sergeant. The 2002 National Defense Authorization Act called for a review of Jewish and Hispanic Army servicemen records, looking for instances where the Medal of Honor was denied due to discrimination. Rubin’s exploits in Korea were reviewed in the process.

On September 25, 2005, President George W. Bush presented 76-year-old Tibor Rubin with the Medal of Honor in a ceremony at the White House. It was the first time since the Korean War that Rubin received any official recognition for his actions in combat and as a prisoner of war. Rubin reflected on what opportunities he may have had if his sergeant had not refused to put him up for the Medal during the war. Not one to dwell on disappointments, Rubin was proud of the life he built with his wife, Yvonne, another Holocaust survivor, and took great pride in knowing what his award meant for the Jewish community.

Kali Schick is Senior Historian for the National Medal of Honor Museum