As Marines charged forward into battle on distant islands during World War II, the inevitable cry of “corpsman!” would ring out. What became an all-too familiar sound of battle represents a unique aspect of the US Navy and Marine Corps. There are no medics in the Navy. None in the Corps, either. Instead, the role of the medic is taken on by the corpsman. Although the rate has evolved over the years, during World War II, enlisted sailors responsible for the care of wounded sailors and Marines were rated as Pharmacist’s Mates but were better known as corpsmen.

Some corpsmen were assigned to the Fleet Marine Force and attached to Marine units to provide medical assistance, particularly in combat. Everywhere Marines went, corpsmen went too, often unarmed, ready and willing to put themselves in harm’s way. To date, twenty-two corpsmen have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the most of any rate in the Navy. One of those recipients is Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class William David Halyburton Jr.

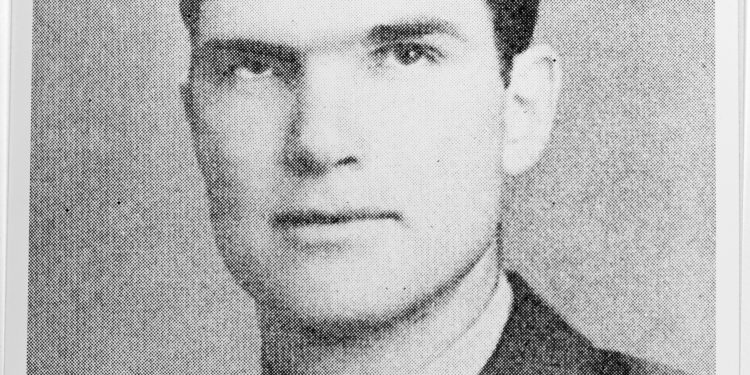

Born in Canton, North Carolina, on August 2, 1924, Halyburton attended New Hanover High School in Wilmington. A member of the school’s ROTC, he also played in the school band and competed on the basketball team. Halyburton was accepted to Davidson College and planned to pursue a career in the Presbyterian ministry. However, like millions of other American men, Halyburton was drafted in August 1943. Allowed to select the US Naval Reserves, he went to boot camp at the Naval Training Station in Bainbridge, Maryland, with further medical training at the Hospital Corps School in the same city. Halyburton advanced to the rate of Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class and continued training at various locations in the United States.

Assigned to the Fleet Marine Force, Halyburton received combat training at Camp Pendleton in preparation for assignment to the Pacific Theater. In December 1944, Halyburton left the United States and joined the Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division. Activated on board the battleship USS Texas BB-35 in February 1941, the 1st Marine Division had gained notoriety for its actions on Guadalcanal in 1942, New Britain in 1943-44, and Peleliu in 1944. Okinawa, which would provide US forces with the fleet anchorage and airfields necessary to invade the Japanese home islands, would yet again test the courage and fortitude of the 1st Division.

On April 1, 1945, Army and Marine Corps units landed on Okinawa. Japanese forces, entrenched in a network of caves and tunnels, put up little resistance at first, but soon unleashed the might of their army on advancing Marines and soldiers. The 5th Marines, fighting their way through the Awacha Pocket on the southern end of the island, had joined the line on April 30. On May 4, Japanese forces launched a major counterattack on American forces in the area. As the Marines fought off the Japanese counterattack, casualties in the 1st Marine Division mounted, including more than 1,400 in the first six days.

High casualty rates created higher risks for corpsmen like Halyburton. As Marines pressed forward, calls for a corpsman came from the direction of the enemy’s fire. Few positions in the military necessitate a person running, unarmed, into harm’s way to save another life. That was the expectation of a corpsman. Those few moments could mean the difference between a bandage and a wooden cross.

On May 10, the 2nd Battalion faced heavy Japanese counterfire as it pushed through a draw in the Awacha Pocket. Hearing calls for a corpsman, Halyburton ran forward, across the draw and up a hill onto a field where Marines were pinned down by heavy fire. Seemingly unfazed by the maelstrom of enemy fire, Halyburton advanced until he reached the farthest wounded Marine and began administering aid. The Japanese fire was concentrated on the area, raining down mortar shells, as machine guns and sniper fire tore through the pinned-down Marines. Halyburton continued to aid the Marine, who was then struck again. Repositioning himself between the wounded man and the oncoming fire, he used his own body to shield the Marine as the fury of Japanese bullets and mortars surrounded them. Halyburton began to take hits, as he continued to aid the wounded Marine. He kept at his work until he was mortally wounded and collapsed on the battlefield.

It was believed that the Marine saved by Halyburton survived, though no one has ever been able to confirm his fate or identify him. Halyburton was only twenty years old when he was killed on Okinawa. Though he was one of more than 12,000 Americans who died in the nearly three months long battle, Halyburton is well remembered still today. In 1984, the guided missile frigate USS Halyburton (FFG-40) was commissioned in his honor and the hospital at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, was named the Halyburton Naval Hospital. A park in Wilmington, North Carolina, also bears his name.

Pharmacist’s Mate Second Class William D. Halyburton Jr.’s courage and sacrifice were the basis of his Medal of Honor action. On May 8, 1946, his brothers Joseph and Robert, both Navy veterans, received the Medal on his behalf. Three years later, Halyburton’s remains were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii. Halyburton’s bravery and selflessness were memorialized in motto of the frigate which carried his name: “Not for self but for country.”

— Kali Martin is a senior historian at The National Medal of Honor Museum