The young man arrived on the University of Alabama campus armed with a high school diploma and a full ride to the state’s flagship institution.

He also arrived clueless.

He had no idea where to go or what to do. He had no parents, guardians, or friends in tow. No class registration, no housing. He just showed up at a school office, asking, so what do I do now?

They didn’t know. So, they called someone who might.

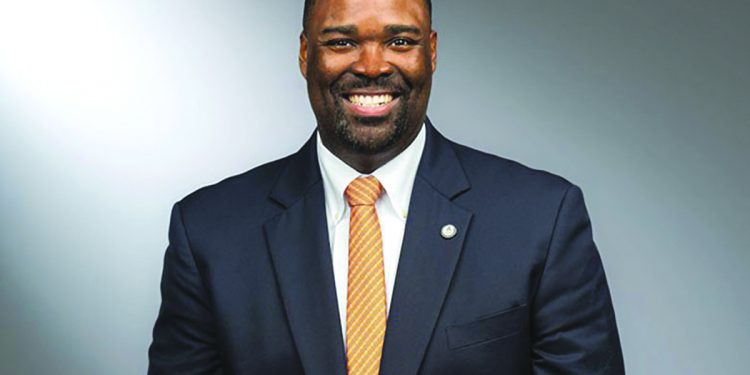

Lowell Davis learned that the young man had come from a children’s home. He was a foster care kid who needed guidance but wasn’t sure where that guidance could come from.

Once kids age out of the system, they’re on their own. Here’s your toothbrush. We wish you well.

“It got me to thinking,” said Davis, then the assistant dean of students and assistant to the vice provost for academic affairs. “How many other students who had aged out of the system were coming to the University of Alabama?”

Davis launched his initiative for the school, Alabama Reach, which helped support students who came to Tuscaloosa with nothing but a backpack and hope.

As Davis’ career took him to other schools, his devotion to former foster care kids went with him. The drill was about the same. Settle into the new job, then launch a similar initiative.

When Davis interviewed for the Director of Student Affairs job at the University of Texas at Arlington last August, he let UTA President Dr. Jennifer Cowley and Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Tamara Brown know upfront that wherever he goes, that passion for ex-foster kids travels along with him.

“Both have caring hearts and spirits,” Davis said over the phone. “Not a day or week goes by without them interacting with me about how we can support this population on campus.”

Those of us outside of that population don’t think all that much about those inside it. The challenges are immense. The young man Davis encountered wasn’t even 17. You have to be 18 to register without a parent’s signature.

“Less than eight percent graduate from college,” Davis said of former foster care students. “They don’t have a place to go during Christmas or spring break.”

Or any break.

“These students don’t know how to navigate the health care system or the college process. What does a credit hour mean? The young man I mentioned couldn’t tie a necktie.”

Thanks to Davis, schools, where he worked, became de facto guardians.

So, it is now at UTA. Davis has hired a program manager, Harold Bryant, who is already partnering with local school districts and county officials to help provide academic, financial, emotional, and social support for those students.

They’re calling it “Emerging Mavericks.”

“We want to reach out to students and expose them to college early so they can see it as a viable option,” Davis said.

What’s heartwarming about Davis’ UTA work is that this is home turf. A Dallas Lincoln product, Davis attended Hampton University to earn a Bachelor of Arts in English, a Master of Arts in counseling, and a doctorate in education, leadership, and policy studies from Indiana University.

The initial plan was to run a counseling center. A professor suggested otherwise when a client took his life, and Davis became intrinsically involved in their lives.

“I was 22 or 23,” Davis said. His professor told him he might be better suited for something else.

“She said there’s no way I can run a counseling center doing things like that every time something happens. It spoke to me.”

He’s found his sweet spot. UTA is the better for it.

“My parents raised us to care, be strong in our faith, and always ask ourselves, what have you done for someone else today?” Davis said. “Having a career in student affairs allows me the opportunity to give back and put into people, make a difference, and make sure that people are better than when I first engaged with them.”

Kenneth Perkins has been a contributing writer for Arlington Today for nearly a decade. He is a freelance writer, editor and photographer.